The Tsar-Confessor

(On the centenary of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich’s assumption of the title of Emperor-in-Exile, 31 August/13 September 1924)

Author of the text: Alexander N. Zakatov

English translation: Russell E. Martin

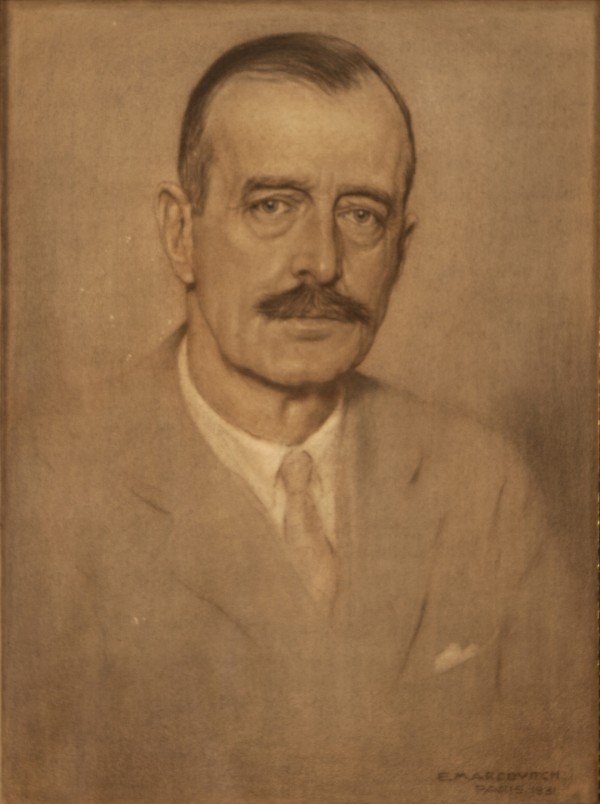

On 13 September (31 August, according to the Julian calendar) 1924, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich issued a Manifesto declaring his assumption of the title of Emperor-in-Exile, in accordance with the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire.

The Manifesto was preceded by several years of reflection, uncertainties, spiritual struggles, and deeply painful emotional experiences.

The revolution that began in February 1917 took the lives of millions in Russia, including all the Romanovs who had not emigrated abroad. Not a single dynastic descendant of Emperor Alexander III in the male line was spared: they were all executed in 1918. When the Bolsheviks officially announced the execution of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearer Emperor Nicholas II, Patriarch St. Tikhon courageously held a memorial service for him and delivered a sermon, in which he denounced the execution of the former sovereign. However, the fate of Tsarevich Aleksei Nikolaevich and Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich was not at first clear. Many believed they might still be alive. Some even cherished the hope that even Emperor Nicholas II was somehow still alive.

That hope was also held for several years by the most senior cousin of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearer, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich. When he assumed the curatorship of the Russian throne on 26 July/8 August 8 1922, he stated in his declaration: “We hope that Emperor Nicholas Alexandrovich is alive, and that the news of His murder was spread falsely by those for whom His salvation poses a threat. Our hearts cannot surrender the hope that He, His Glorious Majesty, will return to His Throne.”

But by 1924 there could be no doubt that the Emperor, his son, and his brother had all been executed in 1918. Kirill Vladimirovich became convinced of this after reviewing the materials provided to him in Nice at the beginning of 1924 by the special investigator N. A. Sokolov, who was investigating the circumstances of the regicide.

Thus, there was no longer a need for a curator of the throne, because, in accordance with the Fundamental State Laws of the Russian Empire, all the rights and duties of the Emperor of Russia had already legally passed to the most senior member of the senior dynastic line of the Russian Imperial House of Romanov, and that person was Kirill Vladimirovich.

The Grand Duke took several more months to consider carefully all the nuances of the situation that now presented itself. As a man of honour, he could not escape the duty that God had thrust upon him. At the same time, Kirill Vladimirovich was well aware that being Emperor was not just a political function, but a sacred office, filled with colossal spiritual struggles and many trials and temptations.

Power was never viewed by the Romanovs as something to be sought, but always as a heavy Cross to bear. And in the case of Kirill Vladimirovich, there was no real power at stake. He was destined to become the successor of his Imperial ancestors not on the majestic throne of a powerful Empire, but in sorrowful and forced exile.

Circumstances, it would seem, gave him the option to refuse to take on the full responsibility of the Emperor—not to expose himself and his family to the dangers associated then with that status. And, indeed, not only his opponents and detractors, but also many people loyal to Kirill Vladimirovich spoke of the “inadvisability,” the “inopportuneness,” and other purely political reasons that should prevent him from officially accepting the title of Emperor.

Nonetheless, his sense of duty prevailed over all these considerations. On 13 September 1924, Grand Duke Kirill signed the Manifesto and ordered it to be made public (1).

Many articles and books have been written about the legal grounds underpinning this Manifesto, about the events that preceded it, and about the process of preparing the text and the fallout it generated. The legal side of the question was and is unassailable (2). In a letter from St. John (Maximovitch) of Shanghai and San Francisco to Tsesarevich Vladimir Kirillovich dated 28 September 1938 (3), St. John offered an assessment of both the positive and negative consequences of the Manifesto of 13 September 1924. St. John, who had not only a theological but also a formal legal education, correctly and precisely noted that “Your Father’s acceptance of the Imperial title had beneficial effects, because it indicated to the Russian people who their Rightful Tsar was, and brought to an end any doubts about the succession to the throne” (4). Political assessments are a matter of opinion and interpretation, of which there can be as many as there are those willing to offer them. At this point it might be useful to focus specifically on the spiritual side of the life and activities of Kirill I.

Members of the Imperial House of Russia were brought up in a strictly Orthodox spirit. Kirill Vladimirovich, his brothers and sister were from childhood (5) instructed in religion by Fr. Alexander Dernov (6), a companion of St. John of Kronstadt. “He was our spiritual guide,” writes Kirill I in his memoirs. “For him I have nothing but the greatest esteem. He was a man of the most profound knowledge and of the most exhaustive culture—a well- trained cleric, who taught us Church history, the catechism, and much else belonging to the scope of his authority” (7).

Other tutors and teachers instilled in Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich’s children a sense of discipline and manual labour (including carpentry), a love for knowledge and culture, and the capacity to appreciate their own values and at the same time understand and respect people of different beliefs. In 1891, Kirill Vladimirovich began classes at the Naval Cadet Corps. The knowledge, skills, and abilities he acquired in childhood were further developed in this far stricter setting, away from the parental home with its atmosphere “of polished manners, of kindness, justice, and exalted moral and ethical standards” (8). It was a harsh, sometimes even cruel school, but it had its benefits: it strengthened his spirit, tempered his character, and expanded his sense of duty and responsibility.

In his memoirs, Kirill Vladimirovich never idealizes the events he describes, nor does he fail to offer criticisms, including criticisms of himself. He remained grateful to his teachers, who prepared him for his life as an adult.

Education is undoubtedly extremely important. But no education can change the essence of a person, inherent in him from birth, inherited genetically. These innate qualities can be either developed and enhanced or, quite the opposite, suppressed and silenced. However, they still remain and come to the surface, especially at critical moments.

Kirill Vladimirovich, like almost everyone in his circle, was a human being and was not immune from the temptations of youth. But his fundamental sincerity helped him avoid deviating from the path determined for him by his Orthodox faith and his dynastic duty.

If we study the biography of Kirill I, not on the basis of scurrilous or satirical sources, or malicious gossip taken out of context, but on the basis of a range of authentic historical sources, a complete and complex image emerges, infinitely distant from the caricature depicted by the slanderers or weak-minded people who are so susceptible to the evil intentions of his enemies.

It is no secret that hateful propaganda has created a monster out of the first Emperor-in-Exile in some corners of the public mind. According this dark and sinister myth, before the revolution, the proud and power-hungry Grand Duke and his family harboured the hope of taking the throne for themselves, intrigued at every turn against Emperor Nicholas II, and then betrayed him during the February-March events of 1917, appearing in the State Duma with a red ribbon. He was, they continue, the “first to flee Russia,” and while abroad, “split the Russian emigration,” becoming a “self-proclaimed emperor.” And he managed to do all this himself, alone and without any support from others, and in the face of hatred and contempt from every direction. That is the myth which, in its baseness, is quite like the slander that had surrounded the memory of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers for many years.

The Nazi propaganda minister Dr. Josef Goebbels openly admitted: “The bigger the lie, the more people will believe it.” Those who follow this principle do not care at all about logic and consistency, nor even the facts. But it is worth considering this point, if only briefly, in order to understand how the dark mythical image of Kirill Vladimirovich is not only false, but also self-contradictory.

Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich’s entire life taken as a whole—both in its heroic moments and in those that sparked controversy—does not in the slightest fit the myth about his “love of power.” With the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War, he immediately went to the theater of military operations, having received the Holy Mysteries of Christ and having said goodbye to his beloved family and friends, knowing that this could well be their last meeting. Calculating, power-hungry people do not act like that. Even in the dramatic story of his struggle for the woman he loved, which caused much bile and bitterness to be flung against him by his critics, Kirill Vladimirovich showed himself to be not at all a man who expected one day to occupy the throne. He understood perfectly that his political and social position would suffer significant damage on account of his entering a marriage that was not initially approved by the Emperor. But he was ready to make sacrifices for the sake of love, precisely because he did not even think about the possibility of his accession to the throne.

Consider the evidence: by a miracle, the Grand Duke escaped death in the depths of the ocean. The troubles he endured because of his marriage to Victoria Feodorovna were overcome. The legal dynastic status of his wife and children was clearly and unambiguously defined by both the State and the Church. His relationship with his cousin the Emperor was fully restored. Indeed, there is no reason to doubt the trust that Nicholas II placed in Kirill Vladimirovich.

The fabrication about the Grand Duke’s “betrayal” in 1917 is one of the most vile and base lies told about him. An entire range of sources irrefutably prove that Kirill Vladimirovich did not wear any “red ribbon,” and his arrival at the State Duma was in fact an attempt “by all and every means to preserve Nicky’s throne” (9).

The Grand Duke did not “flee,” but, on the contrary, was in fact the ONLY one of all the surviving members of the House of Romanov who did not purposefully leave Russia (that is, consciously decide to leave the country), but found himself on a part of the territory of his native country, the Grand Duchy of Finland, that had declared independence. And he remained in Finland for several years, at tremendous risk to his own life and the lives of his family, in the hope that he could somehow, someway help his countrymen.

The charge about his “self-proclamation” as Emperor is also absurd. All the Emperors of Russia were “self-proclaimed,” in the sense that there was no other person or institution to issue the proclamation of a new Emperor except the new Emperor himself, ascending the throne after the death of his predecessor. This is not only his right, but also the duty of each Emperor by virtue of Articles 53 and 54 of the Fundamental State Laws of the Russian Empire (10).

The charge that he caused a “split in the Russian diaspora” is no less absurd. Kirill Vladimirovich acted in accordance with the Fundamental Laws, and it was rather those who ignored the Laws, or offered a distorted interpretation of them, or openly repudiated them, who were the ones sowing discord and disunity. In reality, it was not Kirill Vladimirovich who took action against those in the Russian emigration who opposed him, but rather these same opponents who set up various initiatives in opposition to the legal and legitimate actions of the Grand Duke. Thus, the Emperor established the Imperial Army and Navy Corps (KIAF) in April 1924, while the White “commanders” created the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS) only in September 1924. But for some reason, the assertion that the KIAF was established “in opposition” to the ROVS has become an absurd “commonplace.” Almost all similar anti-dynastic propaganda is based on such deceptions and distortions. And each of the deceptions and distortions crumbles to dust at the slightest scrutiny and analysis.

What was Kirill Vladimirovich really like? Of course, to present him as an angel in the flesh would also be a distortion and an absurdity. One can find in his life many sins, mistakes, and weaknesses. These should be written about and discussed, to be sure. But it would only be honest and accurate also to pay tribute to his many positive qualities, especially as we mark the 100th anniversary of his accession to the position of head of the dynasty according to the Fundamental Laws.

Memoirs from the period depict Kirill Vladimirovich as a modest and sensitive, even shy, man, completely void of the pride falsely attributed to him. St. Nicholas of Japan (11), for example, mentions several times in his diaries a small but revealing detail—that the Grand Duke declined at church services to stand on the rug laid out for him as a sign of respect for a Romanov dynast (12). A later description of Kirill Vladimirovich’s communication with St. Archbishop Nicholas (Kasatkin)—containing both the archpastor’s admonitions and praise—offers a very sincere and simple image of the Grand Duke.

The Emperor’s closest associate, the Director of his Chancellery in exile, G. K. Graf, noted a characteristic trait in Kirill Vladimirovich: he was averse to saying or doing anything negative to his staff, even if a chastising remark or decision was wholly fair and appropriate. Doing or saying something that might upset other people, even if they had made a mistake or had betrayed a trust placed in them, was enormously uncomfortable for him, and so he rarely did it (13).

In matters concerning his activities, and especially in matters that touched him personally, Kirill Vladimirovich often showed humility and hesitation, fearing that his motives might be misunderstood, or that the consequences of his actions might produce controversy. But having made a decision, and having convinced himself of the rightness of it, the Emperor remained steadfast and courageous. When Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich unleashed his attacks on Emperor Kirill Vladimirovich, exploiting the maternal feelings of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, who had never fully reconciled herself to the thought that both her sons and grandson had perished, the Emperor firmly replied: “The dictates of duty and law are above family ties and individual opinions, which, in this case, are the opinions of both senior members of the Imperial House. Just as I was not given the option to take into account whether or not I myself wished to accept the hereditary burden of representing Russia and defending it from the machinations of evildoers, so no one has the right to condemn my actions, which are rooted solely in my desire to do good for Russia. Since I came to have no doubt about the deaths of the senior members of our House, I was obliged to take their place and raise the banner torn from their hands: such is the law, such are the precepts received by me from my sovereign ancestors. I cannot be restrained by the possibility that the future structure of the government will be decided only by the will of the people. In fulfilling the law, I do not violate the true will of the people. I have declared that I am the Emperor by law. When God allows His people freely to express their feelings, let them, grounded in their own spiritual rebirth, and knowing who their Legitimate Emperor is, stand around him to defend the welfare of the Church and the nation. I also declare that the Imperial House lives on, strong in the observance of the statute bequeathed by our ancestors and my lawful accession to the throne. The Church will not reject the Charter that was solemnly placed on the throne of the Assumption Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin by the Russian Tsars, the faithful guardians of Orthodoxy. God’s truth and the historical covenants of the people stand with us. Let not the faithful sons of Russia be disheartened by the obstacles that we encounter on the difficult but holy path we have chosen” (14).

The first place in Kirill Vladimirovich’s worldview was occupied by his Christian values and devotion to the Orthodox Church, which he called “the cornerstone of faith upon which the existence of Russian statehood is based” (15). His faith was not ostentatious or showy, but simple, sincere, and deep. Having inherited the duties of preserving the ideal of the Monarchy, he cared no less for the Church. From his very first addresses that he issued after his accession to the headship of the dynasty, the Emperor called upon the people to fall upon the mercy and help of God, to strive to overcome division and rancor (16), to forgive others and to repent, and for themselves to ask for forgiveness of others: “We will not hide our sins: there was much of it in Rus’. We have paid the highest price for our collective guilt; the Lord’s punishment has brought us to our senses” (17).

Under his initiative, a draft “Regulations on the Orthodox Russian Church” was written in 1926, which sought to clarify and reframe the relationship between Church and State in Russia (18). On 20 July 1926, the Synod of Bishops in Sremski Karlovci “recognized it as desirable and expedient to implement this draft document concerning the Orthodox Russian Church upon the restoration of the monarchy in Russia” (19).

The “symphonia” (a Greek term for the harmony and mutual respect that ideally characterized the relationship between the Church and State in Byzantium—trans.) of Church and State is a Christian ideal. In reality, however, issues could arise even in those times when relations between Church and State came closest to that ideal. During the new Time of Troubles especially, complete harmony in Russia could hardly be maintained in a nation so tormented by strife and revolutionary disorder. However, within a few years, the relationship between the Church and the dynasty returned to normal. On the 5th anniversary of Kirill Vladimirovich’s acceptance of the Imperial title, the First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky), addressed his flock with a call “to commit themselves, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, to our legitimate Tsar, Kirill Vladimirovich, and his lawful Heir, Vladimir Kirillovich” (20). The Metropolitan’s example was followed by the majority of the archpastors and pastors of the Orthodox Russian Diaspora, including those who initially showed hesitation or even some hostility to the legitimate heir of the Romanovs, or even to monarchy itself.

That the initial reaction of some to Kirill Vladimirovich’s Manifesto was negative is quite understandable. After all, many did not accept even the King of Kings Himself, because they expected the Messiah to appear in greatness, splendour, and glory. It was not therefore unexpected that some “looked for a sign” to herald the coming of the earthly tsar. Many Russians, who were accustomed to the beauty and extravagance of the Russian Imperial Court, could not warm to the idea that it was necessary to serve the Legitimate Tsar, even if he did not rule a sixth of the world’s land surface from the Winter Palace, but lived in modest conditions in forced exile. People expected something eye-popping, some kind of miracle. For example, Archbishop Nestor (Anisimov) literally expressed this view in 1926, writing: “Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich’s declaration of himself as Emperor is not broadly accepted, because the people are waiting for instructions from Above in this important and serious matter”(21).

Time passed, and sincere and thoughtful people remembered the words of Christ the Saviour: “An evil and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign; and there shall no sign given to it, but the sign of the prophet Jonah.” (Matthew 12:39). The very same Archbishop Nestor (Anisimov) in a sermon in 1934 on the name day of Emperor Kirill I said: “The Feast Day of Saints Cyril and Methodius is a solemn and sacred day for every Russian, for this holiday is a holiday of the founding of the Russian language, of Russian writing, of great Russian literature, everything most sacred and precious in our national life, and now it is also the name day of the Emperor, who takes upon himself the terrible burden of the Great Banner of Faith, Tsar and Fatherland in these uniquely difficult times”(22). In his correspondence and during liturgical commemorations, Archbishop Nestor invariably called Kirill Vladimirovich the “Pious Great Sovereign Emperor” (23). Nothing had changed in Kirill Vladimirovich’s situation since 1926: he was still living in exile; his financial situation had, if anything, gotten even worse; he could not reward his supporters with either wealth or position; and no visible miracles or signs from Above had manifested themselves. The real and genuine miracle that had occurred was simply this: the people had come around to reality. They had stopped expecting some special new “instructions from Above” and had accepted the instructions ALREADY given from Above—to remain faithful to the people’s vows at the Assembly of the Land of 1613, to their own oaths, and to the legitimate order of succession to the rights and duties of Emperor.

The outstanding liturgist Bishop Gabriel (Chepur) beautifully expressed the feelings of the majority of Orthodox Russian people of the Russian Diaspora: “Your Majesty! The Russian Diaspora is happy that, by the grace of God, He has raised up an Orthodox Autocrat in our midst. The horrors of these Hard Times are no longer so unbearable for the Russian heart: it has found its Tsar and now rejoices, and this heart races with love for him. Great and life-giving is the idea embodied in Your Majesty: the idea, by the grace of God, must conquer everything and open for us our sought-for return to our native land, which will then rise in spirit under your scepter, Great Sovereign! God once saved your life for the good and happiness of Russia... Moved by the contemplation of the great deeds of Heaven, which will be accomplished by Your Majesty, and warmed by the love of our Lord, who so favoured you, I accept the archpastoral duty to place my loyalty at the feet of Your Majesty. God save the Tsar” (24).

Kirill Vladimirovich had a particularly special relationship with Holy Mount Athos. There, on the basis of the Brotherhood of Russian Cells in the Name of the Queen of Heaven, the Monastic Monarchical Organization was formed, which provided the Emperor-in-Exile with fervent intercessory prayers and invaluable moral support.

The First Hierarchs of Local Orthodox Churches similarly treated the Emperor-in-Exile with respect. The Serbian Patriarch Barnabas (Rosich) offered, in his own words, “his humble prayers before the throne of God for the establishment of your monarchy by His all-powerful right hand over the Russian Land” (25).

In the spring of 1931, Kirill Vladimirovich became the first Russian Emperor to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (26). He visited the Church of the Ascension, worshipped at the Holy Sepulcher, processed along the Way of the Cross, prayed in Gethsemane (in the burial cave of the Mother of God and before the relics of the Holy Royal Martyr Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna and the nun Barbara), visited the Eleona Convent and Gornensky Convent, and met with Patriarch Damian of Jerusalem, who later sent the Emperor-in-Exile a gold cross with fragments of the Honorable and Life-Giving Cross of the Lord. In a rescript Kirill I later issued to express his thanks, he wrote to the Patriarch: “This relic and your blessing give me strength for my difficult life’s course and emboldens me to continue the struggle for the Orthodox Faith, which has been desecrated in my homeland, and for the salvation of my people” (27).

Kirill Vladimirovich deeply regretted the divisions and schisms that had afflicted the Holy Church. He himself visited churches of all three jurisdictions and repeatedly called on the hierarchs to overcome their differences and unite. His last official decree was also dedicated to church unity: the Address of 10 August 1938 to the II All-Diaspora Council, which included clergy and laity and took place between 14 August and 24 August 1938 in Sremski Karlovci.

Contrary to the opinions of many émigrés, Kirill I in this Address repeated his unwavering view that, despite all the upheavals, terror, and anti-religious persecution in Russia, the Russian people had not lost their spiritual and historical purpose: “The Orthodox faith,” he wrote, “has not dried up in Rus’, but has only been purified and strengthened. In this lies the guarantee of Russia’s salvation and the visible presence of the merciful Right Hand of the Lord” (28).

Having been met with hostility, lies, and betrayal, Kirill Vladimirovich himself did not feel any lasting resentment towards anyone. He might well feel outrage by the news of some foolish or senseless act, but he never held any malice in his heart. And he did not say a bad word about anyone: neither about his relatives who had taken the path of opposition to him, nor about other people who had purposefully or unknowingly lined themselves up against him. The rare criticism that might occasionally come from him was always fair, measured, and for good cause. His criticism could sometimes be slightly ironic, but was also always gentle and mild.

Possessing a subtle sense of humour, Kirill Vladimirovich displayed no pomp or ostentation when it came to describing himself. He often jokingly spoke and wrote about himself, humbly and honestly admitting his own foibles. But at other times, at critical moments, he showed genuine heroism and self-sacrifice. After an explosion ripped through the battleship Petropavlovsk, hurling Kirill Vladimirovich into the icy waters, he managed to overcome the downward pull of a giant whirlpool and grab onto a piece of the roof of a steam launch; yet though concussed, confused, and burned over large parts of his body, he shouted to his would-be rescuers who found him: “I’m all right! Save the others!” Any thinking person capable of normal human feelings would understand that, in those dire conditions, this was not some “false and showy display,” not some self-promoting gesture, but a reflexive act arising from the heart and from the depths of his character.

Kirill I’s abiding concern was to restore the good name of those who had been unjustly slandered and reviled. He defended the honour and memory of Emperor Paul I (29), Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (30), and Vice-Admiral Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky (31); and he even considered it necessary to stand up for Gregory Rasputin, who had been demonized by rabid propaganda (32).

Even more significant: it was Kirill Vladimirovich who raised the question for public discussion, at the very highest levels, of the fate of the remains of the Royal Martyrs (33); and together with Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) officially laid the foundations for their veneration and eventual canonization by signing on 11 July 1929 a Decree designating the day of the regicide, 4/17 July, the “Universal Day of Mourning of the Russian People” (34).

The patriotic and philanthropic activities of Emperor Kirill I, which I describe in greater detail in my other works, were imbued with a Christian Orthodox spirit. Faith in Christ the Saviour underlay everything he did. This priority precluded the use of the Name of God as just some means to achieve some goal, be it even the most praiseworthy social, political, or cultural goal. For the House of Romanov, the Orthodox Church is not some ancillary institution, not an ideological department, not an ally in a struggle FOR or AGAINST some or other purpose, but the Body of Christ Itself—the WAY, the TRUTH, and the LIFE.

In his twilight years, the Emperor-in-Exile suffered bitter losses and a painful illness. In 1936, both his beloved wife, Empress Victoria Feodorovna, and his faithful spiritual friend and mentor, Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky), passed away. In 1937, the Serbian Patriarch Barnabas also passed away. The Emperor’s own health rapidly began to deteriorate as well, due to the lingering side effects of the hypothermia he experienced on 13 April 1904, which led to the development of arteriosclerosis. Kirill I suffered greatly from constant pain, insomnia, and progressive loss of vision. He endured all these ailments and sorrows patiently and without complaint, according to the words of the Lord’s Prayer, “Thy will be done.”

In August 1938, signs of gangrene appeared on Kirill Vladimirovich’s leg. Doctors determined that the condition was inoperable. On 22 September, the Emperor-in-Exile left his last earthly refuge, the Ker Argonid house in Saint-Briac, for the hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris. There his family and friends gathered around him, including his brother, Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich, with whom he had previously had a falling out because of the latter’s morganatic marriage (35).

On 10 October, Kirill Vladimirovich took Confession and received Holy Communion from his father-confessor, Father Vasily Timofeev. The next day, the Emperor’s condition worsened and by evening he had lost consciousness. On 12 October 1938, at 1:15 p.m., one day before his 62nd birthday, Emperor Kirill I surrendered his soul to God. The circle of his life was now complete.

The funeral service for the Emperor Kirill I Vladimirovich was held on the Feast of the Intercession of the Mother of God, October 14—not in the resplendent cathedral in Paris on rue Daru, but in the comparatively modest Church of the Sign of the Most Holy Theotokos on rue Boileau, which, in a way, was more appropriate for Kirill Vladimirovich, given his humility and piety. Archbishop Feofan (Gavrilov) brought the Virgin Hodegetria icon of the Russian Diaspora—the Kursk Root Icon of the Mother of God. On 18 October 1938, the body of Kirill I was interred in the Mausoleum of the Dukes of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, next to his wife.

Fifty-seven years later, in 1995, Emperor Kirill Vladimirovich’s daughter-in-law, the Dowager Empress Leonida Georgievna, arranged for the remains of her father-in-law and mother-in-law to be reburied in the Mausoleum of the Ss. Peter and Paul Cathedral, where their son, Grand Duke (and de jure Emperor) Vladimir Kirillovich, had already found eternal rest in 1992. When the tomb was opened in Coburg on March 3, the remains of Empress Victoria Feodorovna were discovered only to be bones, but the body of Emperor Kirill I was found to be incorrupt. On 7 March 1995, the Imperial couple were reburied in St. Petersburg in the presence of the entire Imperial Family: the Head of the House of Romanov, Grand Duchess Maria of Russia; her mother, Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna; and Tsarevich George Mikhailovich (36).

* * *

The Orthodox Church discourages excessive enthusiasm for numerology and the harmful desire to see hidden signs and encrypted messages in numbers or combinations of numbers. At the same time, there is such a thing as biblical numerology, and some coincidences of historical dates and church feast days undoubtedly have a spiritual significance (37). As theologians explain, numbers from the point of view of Christianity are not sacred, but they can be symbolic. It is certainly not a coincidence that the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 took place on the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, that the victory in the Battle of Poltava became a kind of gift for the name day of Tsar Peter I, and that the Battle of Borodino took place on the Feast Day of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God. It is a Russian tradition to build churches in honour of saints on whose feast days the Tsars and Emperors were born (for example, St. Isaac’s Cathedral and the Admiralty Cathedral of St. Spiridon in St. Petersburg). The Holy Royal Passion-Bearer Emperor Nicholas II attached great importance to the fact that he was born on the Feast Day of the Holy and Righteous Job the Long-suffering. There are likewise several very important symbolic coincidences in the life of Kirill Vladimirovich.

He was born on 30 September/13 October 1876, on the Feast Day of King Edward the Confessor (38). Edward’s name does not appear in the Orthodox calendar of saints, because he was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, in 1161, after the Great Schism with the Orthodox Church. However, this does not change the fact that King Edward of England, who went down in history with the title of CONFESSOR, which is rare for monarchs, ruled before the Great Schism and was therefore an Orthodox sovereign—a pious patron of the Church, who knew exile and many hardships and sorrows.

Even more symbolic was the rescue, mentioned above, of Kirill Vladimirovich during the sinking of the battleship Petropavlovsk. This catastrophe took the lives of the commander of the Pacific Fleet, Vice-Admiral S. O. Makarov, the artist V. V. Vereshchagin, and most of the crew. No one standing next to the Grand Duke on the bridge survived. But he, in an absolutely miraculous way, was not killed by the explosion that tore through the ship, and he escaped from the deadly whirlpool that formed around the rapidly sinking vessel. This all happened on 31 March/13 April 1904, on the Feast Day of the Holy Martyr Hypatius of Gangra, one of the principal Heavenly patrons of the House of Romanov. It will be remembered that it was at the Ipatiev Monastery in Kostroma on 14/27 March 1613 that the founder of the Romanov dynasty, Tsar Mikhail I Feodorovich, was called to the throne. Saint Hypatius, who during his lifetime performed miracles with both fire and water, appeared on 31 March/13 April 1904, amidst the flames and water, to save the life of the one who was destined 20 years later to announce to the world that the House of Romanov had not perished in the new Time of Troubles and had not abandoned its ideals.

In world history, we see many different types of monarchs: warrior-kings, diplomat-kings, reformer-kings, unifier-kings, builder-kings, philosopher-kings, and martyr-kings. Each era has its own kind of king. In his service as Head of his Imperial House, Kirill Vladimirovich’s role as a confessor-king came to the fore.

The word “Confessor” implies, first of all, enduring persecution for the true faith in Christ, which did not result in death (as in martyrdom). At the same time, one finds in the works of the Holy Fathers and theologians a broader interpretation of the term. Confessors are Christians who have given witness to their faith by their deeds and have been subjected to vilification, exile, the mockery of heretics, and hostility from their brother-Christians.

It is in this broad sense that King Edward is known to history as a Confessor, and in the same sense, that Emperor-in-Exile Kirill deserves this title, as well.

The words of the Holy Martyr Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov), addressed in his own day to Emperor Nicholas I, perfectly apply to him: “Even from his birth, the Lord destined for the throne the one whom no one expected in the order of succession, but who was blessed with the will necessary to bring those in error to reason” (39).

Having inherited his role as head of the dynasty in fundamentally different conditions from his predecessors, and not possessing any real power other than what the Law supplies, or any real influence other than the power of words, Kirill I professed the Orthodox understanding of monarchical power based on Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition, and fully set out in the works of St. Philaret of Moscow, St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, and St. Seraphim of Boguchar. He professed the principle of symphonia between Church and State as formulated in St. Emperor Justinian’s Novella 6 (40). He professed the sacredness of the vow of the Assembly of the Land of 1613 about the connection between the House of Romanov and the Russian people “unto generations and generations”(41). Literally until his last days, Kirill Vladimirovich served the cause of restoring the unity of the Russian Orthodox Church. He also professed the holy optimism common to all Orthodox Christians: “to drink the bitter cup of life to the end in the hope that, after Golgotha, the Resurrection will come” (42).

The Emperor could say, as did the Holy Apostle Paul: “We are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed. (...) By honour and dishonour, by evil report and good report: as deceivers, and yet true; as unknown, and yet well known; as dying, and, behold, we live; as chastened, and not killed; As sorrowful, yet alway rejoicing; as poor, yet making many rich; as having nothing, and yet possessing all things" (2 Cor. 4:8-9 and 6:8-10).

The sufferings sent to Kirill I at the end of his earthly sojourn served to atone for the sins that he, like any person, could not avoid in his life. The Lord granted His servant a truly Christian death: reconciliation with those with whom fate had previously separated him, and a deathbed Confession and Communion of the Holy Mysteries of Christ. The remains of Kirill Vladimirovich were moved more than half a century after his death to his homeland; and when the coffin was opened, they were found to be incorrupt.

The question of glorifying someone as a saint can only be decided by a council of the Church, based on a thorough study of all the circumstances of a Christian’s life. Holiness does not mean sinlessness or faultlessness. Recognizing someone as a saint by the Church does not mean that the saint should never be the object of empirical study, so that the person is never examined from a historical or empirical perspective. And, certainly, not all saints have been officially canonized by the Church. For any number of reasons, not all righteous people and national heroes can be counted among the saints. Some saints (as, for example, the Holy Blessed Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy) were included in the Church’s calendar of saints only several centuries after their death. Sometimes, general grassroots veneration precedes local or Church-wide canonization. Other times, it is the determination of a Church council that gives rise among the Christian flock to the popular veneration of holy monastics, bishops, pious princes and tsars, or other ascetics. In the case of so many holy men and women, we must be humble, patient, and obedient to our Archpastors and pastors, waiting on their inspired determination. But it is certain that many of the monarchs of Russia, including those not included in the calendar of saints today, served God and their people honestly, selflessly, and righteously, and are worthy, at the very least, of devotion and honour, and of our fervent prayers for their immortal souls.

Among these pious princes and tsars who are yet to be canonized is surely numbered Emperor-in-Exile Kirill I—the Confessor of the Cross-Bearing Orthodox Realm, which is the earthly and temporal icon of the Eternal Heavenly Kingdom of Christ.

***

NOTES

- Kirill I was not the first to adopt a royal title while in exile. Other royals had done the same in their own times, including King Charles II of England and King Louis XVIII of France. “Louis XVIII…,” wrote François-René de Chateaubriand, “was King everywhere, as God is God everywhere, in the nursery or in the temple, at an altar of gold or an altar of clay. Adversity did not force him to make even the smallest concession; the more fate humiliated him, the higher he raised his head; his name served as his royal crown; it seemed as if he were saying: ‘You can kill me, but you cannot kill the centuries written upon my brow’.” François-René de Chateaubriand, Zamogil’nye zapiski [Mémoires d’outre tombe], translated into Russian from French by O. E. Grinberg and V. A. Milchina (Moscow: Sabashnikov Publishers, 1995), 289.

- See A. N. Zakatov, “Otrechenie ot prestola i obespechenie dinasticheskoi preemstvennosti v rossiiskom prave,” in Sistematizatsiia zakonodatel’stva i dinamika istochnikov prava v istoricheskoi retrospektive (k 380-letiiu Sobornogo ulozheniia): sbornik nauchnykh trudov, ed. D. A. Pashentsev and M. V. Zaloilo (Moscow: Institut zakonodatel’stva i sravnitel’nogo pravovedeniia pri Pravitel’stve Rossiiskoi Federatsii: INFRA-M, 2020), 100-116 (available here: https://proza.ru/2020/10/23/1636); and idem, Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii. Bliustitel’stvo (1917-1924): nauchnaia monografiia (Moscow: INFRA-M, 2023) (available here: https://imperialhouse.ru/rus/monograph/articles/3977.html).

- Written as Emperor Kirill I lay on his deathbed.

- Archive of the Russian Imperial House (ARID), fond 8, opis’ 1, delo 74.

- From 28 January 1884 until 6 May 1899.

- Alexander Dernov (1857-1923), future archpriest and rector of the Ss. Peter and Paul Cathedral (which also served as the family mausoleum of the House of Romanov), and then (beginning in 1915) protopresbyter and head of the Clergy of the Imperial Court. It was Protopresbyter Alexander Dernov who baptized Vladimir Kirillovich, the son and heir of Kirill Vladimirovich, on 18 September 1917. He arrived from Petrograd with the Reader V. Ilyinsky for that purpose, and brought two family heirlooms: a silver baptismal font and a genealogical book. See Vladimir Kirillovich and Leonida Georgievna, Rossiia v nashem serdtse [Russia In Our Hearts] (St. Petersburg: Liki Rossii, 1995), 14. See also: https://imperialhouse.ru/rus/monograph/monograph/vladimir-kirillovich-glava-rossijskogo-imperatorskogo-doma-e-i-v-gosudar-velikij-knyaz-leonida-georgievna-e-i-v-velikaya-knyaginya-rossiya-v-nashem-serdtse-spb-liki-rossii -1995-160-s.html.

- Kirill Vladimirovich, Moia zhizn’ na sluzhbe Rossii (St. Petersburg: Liki Rossii, 1996), 44. [The English translation is taken from Grand Duke Cyril, My Life in Russia’s Service (London: Selwyn and Blount, 1939; reprint: Royalty Digest, 1995), 24.] See also: https://imperialhouse.ru/rus/monograph/monograph/kirill-vladimirovich-imperator-moya-zhizn-na-sluzhbe-rossii-spb-liki-rossii-1996-334-s.html.

- Kirill Vladimirovich, Moia zhizn’ na sluzhbe Rossii, 55. [The English translation is taken from see: My Life in Russia’s Service, 35.]

- Correspondence between Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich and Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (hereafter: GARF), f. 601, op. 1, d. 2098. See Zakatov, Imperator Kirill I v fevral’skie dni 1917 g. (Moscow: Izdatel’skii tsentr “Novyi vek,” 1998), and online: https://proza.ru/2011/02/25/703.

- Article 53: “On the demise of an emperor his heir accedes to the Throne by virtue of the law of succession itself, which confers this right upon him. The accession of an emperor to the Throne is counted from the day of the demise of his predecessor.” Article 54: “In the manifesto on accession to the Throne the rightful heir to the Throne is also named, if a person to whom succession belongs by law exists.”

- Whom the Grand Duke had met in 1898 while visiting Japan during his deployment on the cruiser Rossiia.

- Dnevniki sviatogo Nikolaia Iaponskogo, T. 3 (s 1893 po 1899 gody) (St. Petersburg: Giperion, 2004), 747 (8 July 1898), 748 (10 July 1898).

- G. K. Graf, Na sluzhbe Imperatorskomu Domu Rossii, 1917-1941: Vospominaniia, edited, bibliography, commentary, and Introduction by V. Iu. Cherniaev (St. Petersburg: Izdatel’stvo “Russko-Baltiiskii informatsionnyi tsentr ‘BLITs’,” 2004), 70-71.

- “Obrashchenie ot 12/25 oktiabria 1924 g.,” in Obrashcheniia glavy Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma Romanovykh, imperatora v izgnanii Kirilla I Vladimirovicha. Ofitsial’nye akty i soputstvuiushchie istoricheskie istochniki, 1922-1938. Sbornik dokumentov. Introduction by A. A. Cherkasov, edited and commentaries by A. N. Zakatov (Washington, DC: Cherkas Global University Press, 2024), 43. Available online: https://cherkasgu.net/images/our_stats/pdf/the-appeals-of-the-head-of-the-russian-imperial-house-of-romanov-of-the-emperor-in-exile-kirill-i-vladimirovich.pdf.

- “Obrashchenie ot 26 ianvaria 1928 g.,” in Obrashcheniia glavy Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma Romanovykh, imperatora v izgnanii Kirilla I Vladimirovicha, 67.

- Zakatov, “Osmyslenie prichin i sledstvii Revoliutsii 1917 goda Rossiiskim imperatorskim domom Romanovykh,” in Stoletie Revoliutsii 1917 goda v Rossii. Nauchnyi sbornik. Chast’ 1, ed. I. I. Tuchkov (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo AO “RDP,” 2018) (=Trudy istoricheskogo fakul’teta MGU, vyp. 108, Series II, Istoricheskie issledovaniia, 60, pp. 30-53). Available online: http://www.hist.msu.ru/about/gen_news/38247/.

- “Obrashchenie ot 2/15 aprelia 1923 g.,” in Obrashcheniia glavy Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma Romanovykh, imperatora v izgnanii Kirilla I Vladimirovicha, 24.

- “Proekt Polozheniia (Zakonopolozheniia) o Pravoslavnoi Rossiiskoi Tserkvi…,” in Obrashcheniia glavy Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma Romanovykh, imperatora v izgnanii Kirilla I Vladimirovicha, 53-55.

- Zakatov, Sviataia Gora Afon: Pravoslavnaia Tserkov i Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii. Istoricheskoe i sotsiokul’turnoe znachenie tserkovno-dinasticheskikh otnoshenii posle revoliutsii 1917 goda. Perepiska afonskikh monakhov i ierarkhov Pravoslavnoi tserkvi s imperatorskoi sem’ei i Kantseliariei glav Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma. Istoricheskie istochniki (1921-2013), 3 vols. (Tallinn: “Assotsiatsiia Rossiisko-Estonsii dialog kul’tur,” 2013), 2:110.

- Published in Tsarskii vestnik, no. 63 (1929) 14(/29) October, in Yugoslavia.

- GARF, f. 6343, op. 1, d. 6, list 138. See also Vernuvshiisia domoi. Zhizneopisanie i sbornik trudov mitropolita Nestora (Anisimova), 2 vols., ed. O. V. Kosik (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo PSTGU, 2005), 2:257.

- Griadushchaia Rossiia, no. 9-10 (1934), pp. 6-7 (published in Shanghai).

- Zakatov, Sviataia Gora Afon: Pravoslavnaia Tserkov i Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii, 3:15. Unfortunately, it is often the case that, when publishing primary sources on the history of the Church and the Russian diaspora, the editors of these publications mention the initial doubts of one or another person as if it were their permanent position, without showing that their opinion had changed over time. To cite one example: “The legitimist movement also existed in China,” writes the editors of a collection of works by Metropolitan Nestor (Anisimov). “However, in general, [legitimism] was not characteristic of the Russian community in the Far East. Archbishop Nestor also did not agree with the legitimists.” (Vernuvshiisia domoi, 1:46). And then the letter of Archbishop Nestor, mentioned by us, of April 20, 1926, published in the 2nd volume of this work (Vernuvshiisia domoi), is quoted in relation to the address of Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) “to commit themselves, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, to our legitimate Tsar, Kirill Vladimirovich, and his lawful Heir, Vladimir Kirillovich,” dated September 13, 1929 (!). This is an obvious manipulation of the facts. After all, in 1926 Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) himself still showed some hesitation about legitimism. Only in 1929 did he completely free himself of his mistaken views on the matter. The majority of the bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad agreed with his new view, including Archbishop Nestor (Anisimov), who recognized Emperor Kirill Vladimirovich as the Legitimate Emperor and even accepted the Order of St. Nicholas from him. Incidentally, the fact that Archbishop Nestor accepted the Order from Emperor Kirill Vladimirovich is mentioned in the same publication (Vernuvshiisia domoi). But only a very attentive reader would notice this contradiction between the historical facts and the words of the editor of this “Biography.” The general impression remains that Bishop Nestor “did not agree with the legitimists.” I would like to address authors of this kind: Dear fathers and brothers, come to your senses. I would myself like to say to authors who engage in this kind of distortion of the facts: Dear fathers and brothers, come to your senses. When you publish these kinds of omissions, distortions, and sometimes even outright falsehoods, you are not only committing historical falsification, but, without exaggeration, you are destroying the foundations of a traditional worldview. All lies are bad. But a lie concerning not just an individual, but concerning the very essence of the Church and its hierarchs’ relationship to the sacred office of monarch and to the one who bears that responsibility at any given moment, is harmfully misleading people about one of the most important elements in the system of Orthodox spiritual values.

- Zakatov, Sviataia Gora Afon: Pravoslavnaia Tserkov i Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii, 2:176-177.

- Zakatov, Sviataia Gora Afon: Pravoslavnaia Tserkov i Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii, 2:260.

- See Graf, Iz putevyh zametok, 2d edition (Shanghai: Russkii prosvetitel’nyi komitet, 1939).

- Zakatov, Sviataia Gora Afon: Pravoslavnaia Tserkov i Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii, 2:286.

- Zakatov, Sviataia Gora Afon: Pravoslavnaia Tserkov i Dom Romanovykh v izgnanii, 3:106.

- “When Paul I was murdered by those who were close to him and owed him their positions and honours, the Russian people, of whose cause he had always been a champion, considered him a martyr, and before the revolution there were pilgrimages to his tomb in the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul. People went there to pray, popular belief invested him with almost a halo of sanctity, and miracles were expected. This was the old-fashioned attitude of Russians to their Emperors, until all this disappeared with the so-called progress and enlightenment.” Kirill Vladimirovich, op. cit., p. 35. [The English is taken from: My Life in Russia’s Service, 15-16.]

- According to Kirill Vladimirovich, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich “had the loftiest principles coupled with a character of the rarest nobility” and “the Revolutionaries murdered him, because, while many of our administrators had lost their heads, he had kept his and had gone about his duty energetically.” Kirill Vladimirovich, op. cit., pp. 33 and 203-4. [The English is taken from: My Life in Russia’s Service, 13, 173.]

- “A brilliant man…Rojdestvenski, then a Rear-Admiral, the defamed hero of one of the great exploits in naval annals, a kind of Hannibal of the Sea, of whom I will have occasion to say a few words later. I consider it my duty to pay tribute to this Russian patriot who sailed to certain doom, about which he had no illusions whatever, with a floating scrap-heap, over twenty thousand miles of sea, unbacked by any base and with the face of the world set hard and sarcastically against him. And when they knew that all was lost, that Port Arthur had fallen, and the armies routed, they met a splendidly equipped enemy born to the sea, and in an unequal contest they perished like men, fighting till the sea closed over them. […] Rojdestvenski was a very capable officer. This he proved by taking the whole of a large fleet in the most difficult conditions possible to a battle at the other end of the world in perfect order, without losing one of his ships and—what kind of ships! This epic feat was properly appreciated later. […] The Admiral acted properly in the dilemma in which he found himself, and no blame is attached to him or to our fleet. Even though our ships were nearly all destroyed in an unequal contest on 27 May 1905 in the Straits of Tsushima, where our ‘tin pots,’ out-ranged and outdone in every conceivable way, put up a heroic struggle and battered the enemy considerably before they were sunk, this epic story of a doomed fleet sailing to certain death and fighting to the very last gasp, after a voyage of unprecedented length, stands alone of its kind among the naval annals of the world. The Admiral had been badly wounded during the battle and was a dying man, and when he was returning to Russia after his captivity in Japan, even the Revolutionaries cheered him and ran up to his train to see the man who had not spared himself. But what did the authorities do with Rojdestvenski? They court-martialled him! For having taken a scrap-heap to order across the sea to Japan and for having lost it there. If this were not true, it would sound fantastic!— they condemned this man for having loyally carried out the Gilbertian plans of their own concoction. Two years later he died broken in body and in spirit.” Kirill Vladimirovich, op. cit., pp. 129, 207-9. [The English is taken from: My Life in Russia’s Service, 103, 177, 178-79.]

- Not idealizing the “holy elder,” Kirill Vladimirovich nonetheless noted that “[i]t may be said to his credit that he had the common sense of a peasant to remain to his end a son of the people to whose cause he was always greatly attached.” Kirill Vladimirovich, op. cit., 224. [The English is taken from: My Life in Russia’s Service, 192.]

- “Obrashchenie ot 8 avgusta 1924 g.,” in Obrashcheniia glavy Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma Romanovykh, imperatora v izgnanii Kirilla I Vladimirovicha, 33.

- “Akt Imperatora Kirilla I i Mitropolita Antoniia (Khrapovitskogo) ot 11 iiulia 1929 g.,”in Obrashcheniia glavy Rossiiskogo imperatorskogo doma Romanovykh, imperatora v izgnanii Kirilla I Vladimirovicha, 72.

- The two brothers had reconciled in a few months before, in July 1938.

- Zakatov, “Netlennaia slava. K 10-letiiu so dnia pereneseniia ostankov imperatora Kirilla Vladimirovicha i imperatritsy Viktorii Feodorovny iz Koburga v Sankt-Peterburg,” in Samarskie gubernskie vdomosti (March 2005). Available online: https://proza.ru/cgi-bin/login/page.pl.

- Biblical numerology is the study of historical and symbolic numbers contained in the Holy Scriptures.

- Edward the Confessor (1004-1066), King of England (1044-1066). Last member of the Orthodox House of Wessex. He was the son of King Æthelred II of England and his Queen, Emma of Normandy. He was renowned for his asceticism, charity, and fidelity to the Church.

- Metropolitan Serafim (Chichagov), Da budet volia Tvoia, 2 pts. (Moscow and St. Petersburg: Palomnik, MP “Neva-Ladoga-Onega” and SP “Riurik,” 1993), 1:123.

- From the Preface of Novella 6: “The priesthood and the Empire are the two greatest gifts which God, in His infinite clemency, has bestowed upon mortals; the former has reference to Divine matters, the latter presides over and directs human affairs, and both, proceeding from the same principle, adorn the life of mankind; hence nothing should be such a source of care to the emperors as the honour of the priests who constantly pray to God for their salvation.”

- Zakatov, “Utverzhennaia (Utverzhennaia) gramota Velikogo sobora 1613 goda kak istochnik prava,” in Sistematizatsiia zakonodatel’stva v fokuse istoriko-pravovoi nauki (k 470-letiiu priniatiia Sudebnika 1550 g.). Sbornik nauchykh trudov, ed. D. A. Pashentsev (Moscow: Institut zakonodatel’stva i sravnitel’nogo pravovedeniia pri Pravitel’stve Rossiiskoi Federatsii: INFRA-M, 2021), 110-19. Available also online: https://proza.ru/2021/05/13/22.

- Kirill Vladimirovich, op. cit., 244. [This quotation does not appear in My Life in Russia’s Service, the English translation of Moia zhizn’ na sluzhbe Rossii. The English version has a very different ending from the Russian version.]

***

ЦАРЬ-ИСПОВЕДНИК | Газета "МОНАРХИСТ" (monarhist.info)

(http://monarhist.info/newspaper/article/127/7387)