Your Imperial Highness, you were born in Spain in 1953 and raised in both Spain and France. What memories do you have of your family life growing up, and what influence did your parents have on you?

My parents loved each other very much and they created an atmosphere of love that surrounded and radiated out from them. To live and grow up in such a loving environment was for me a source of great happiness.

Even so, I cannot say that I was raised a spoiled child or that I got everything I ever asked for. Both my mother and father could be rather strict and demanding on me when they needed to be. For example, they insisted very firmly that I diligently study the Russian language. Far from all royal families living in exile make the same demand to study their native language on their younger generations.

And there were other limitations and demands placed on me, both religious and moral. And more than anything else, my parents instilled in me the firm belief that our position as members of the Romanoff dynasty is first and foremost a duty, not a right. They taught me that we are not ordinary private individuals but that our lives belong, in a very real way, not to ourselves but to our country—to Russia.

My parents never doubted that the day would come when we would have the opportunity to return to our homeland. They maintained this firm belief even during the most hopeless of times, when the Communist regime outwardly seemed firmly entrenched in power. All their beliefs and their genuine sense of optimism they passed on to me. Perhaps it happened that way because, even when they were being strict, they had so much love and they conveyed their faith and their ideas to me not through threats and punishments, but by their personal example, their patience, and their instruction.

After the death of your grandfather, Emperor-in-Exile Kirill Vladimirovich, your father, Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich, became the Head of the Russian Imperial House and gave more than 50 years of his life to the service to Russia. How would you like history to remember him?

The Lord entrusted both my grandfather and father with the mission of preserving the ideal of the Russian Orthodox legitimate monarchy in a terrible time, when the entire system of traditional values was being destroyed by violent and bloody means.

I would want my countrymen to give a just and fair assessment to the sacrifices made by my father and grandfather, and that they would share the view of my father expressed by His Holiness Patriarch Aleksei II of Moscow and All Russia at my father’s funeral in St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg: “He spent his entire life outside Russia, moving from country to country. But he never felt at home in any of these lands, for his thoughts and feelings were always reaching back to his country, which he always considered his true homeland. He never accepted the citizenship or adopted the nationality of any other country. He believed that his only reason for being was to serve as best he could his homeland. He considered it a sacred duty, and during his entire life, much of it filled with hardships and sorrows, he fulfilled his duty, as he understood it, as best he could.”

Your mother, H.I.H. The Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna, was born into the Georgian Royal House. She was involved in many charitable and cultural activities over the years. How would you like history to remember her?

My mother was a faithful, loyal, and devoted companion to my father. In our family life, she was the personification of the old Georgian adage: “The husband is the head, but the wife is the neck.” Of course, my father was the head of the family, but my mother always remained the "neck“—always holding him upright and, on occasion, helping him decide to turn this way or that.

She never forgot, though, that she was a member of the old Georgian dynasty and she love Georgia all her life. But the interests of Russia and the House of Romanoff were first in her heart. My mother was an extraordinarily kind person—sensitive, cheerful, and intelligent. Many of those who met her, even those who were predisposed against us, went away from their encounters with her with a different opinion of us and a new appreciation for our family and our work, even if they never in the end shared our views.

My mother was—not only in my opinion but in that of many who knew her—the very epitome of the Tsaritsa-Mother, an image that has remained in the popular imagination for centuries. That image is all the more warm and touching in that it preserves the monarchist ideal of the Family-State.

Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich and Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna visited Russia in November 1991 on the invitation of the mayor of St. Petersburg, Anatoly Sobchak. From a historical point of view, how was this visit important for the Russian Imperial House?

When my father received the first invitations from Russia—or, as it was at that time, the USSR—many of our countrymen living abroad actively tried to dissuade him from going. A group from the US led by Archbishop Antonii (Sinkevitch) went to my father to convince him not to go. They said that Russia remains a Communist country, that everything there was still under the control of the KGB, that lies and falsehood resided there, that the Church was not the true Church, that the people were not true Russians, that if the Head of the House of Romanoff were to accept this invitation from the Communists, he would be betraying everything he believed and upheld, and so on and so forth.

But my father stood firm: If my country needs me, I must go. True, many things were still complicated, unhealthy, and unclear about Russia at that time, but we have no other homeland, and we never will. As our Lord and Saviour put it, it is the sick, not the healthy, who have need of a doctor. And if there are problems in our country, and we can in any way help, and our countrymen are calling upon us to offer that help, our duty is to be with them.

Moreover, my father all his life had dreamed of the day when he could see Russia, the land his parents had told him so much about. He was no longer a young man and his health was not perfect. And he felt in his heart that the Lord had sent to him—precisely to him, in the twilight of his life—the opportunity to help bring our ideals and principles, our legacy and wealth of experience, back to our country.

Therefore, he could not agree with those who opposed his trip and decided to go. My mother fully supported him in this decision and helped him deal with the emotional reactions of those who could not understand the profound significance of this historical moment.

Because my father made his first visit to Russia since the Revolution precisely then, in November 1991, it will forever be known in the history of our country and our dynasty, that the Head of the House of Romanoff and his spouse did not give in to the biases of some in the émigré community, did not calculate the possible political benefits of their trip, did not dither and did not inflate their own importance, but immediately and with an open heart rushed to their homeland at the very beginning of a new stage in its history.

Certainly, after the fall of the Communist regime, the process of reintegrating our House into the social life of the country would begin sooner or later, one way or another. But I am grateful to God that it began this way, with their visit in November 1991, and that my father would be the one destined to mend the torn fabric of time.

Your grandfather, Emperor-in-Exile Kirill Vladimirovich, has been on occasion accused of disloyalty. His detractors claim that in 1918 he swore allegiance to the new Provisional Government and that he wore a red armband on his uniform, even though there were no reliable witnesses of any of this and he firmly denied these accusations in his memoirs. Can you comment on this accusations?

Slander has always been one of the most effective weapons of the unprincipled politician.

Even your question itself makes the point, quite correctly, that that there are no authoritative witnesses or reliable evidence of any of the alleged actions some claim my grandfather took during the Revolution.

The correspondence between my grandfather and his uncle, Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich, in February and March 1917, which is preserved in the State Archive of the Russian Federation and which has been published numerous times, makes it clear that they together strove “with all their strength and in every way possible to preserve Nicky [that is, Emperor Nicholas II] on the throne.”

It’s certainly possible that they did not fully appreciate the gravity of the situation and therefore made a number of mistakes and miscalculations, but there was without any doubt never even the slightest hint of disloyalty in their actions.

Neither my grandfather nor Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich served the Provisional Government. They resigned their official positions and offices after the illegal arrest of the Imperial Family.

This fiction about the “red armband” and other slanderous claims began to spread only after my grandfather assumed the responsibilities that he legally inherited for the fate of the dynasty in exile.

And of course, it is hard to imagine how it could have been otherwise. It would be surprising and highly unusual if the Head of the dynasty didn’t become the target of mendacious attacks.

After the Bolsheviks came to power, there arose a whole range of political groups outside of Russia that were all preparing for another revolution in Russia. The cynical leaders of these parties had a lot of experience slandering the dynasty. On the extreme left, they hated the monarchy no less than even the Bolsheviks did, and the February conspirators saw the monarchy at best as no more than a kind of figurehead. On the extreme right, these leaders imagined themselves as “more monarchist than even the tsar” and felt they could control the monarch like a puppeteer does a marionette. Of course, they were all annoyed when the senior member of the House of Romanoff was not afraid to accept his inherited rights and duties and to adopt independent positions on issues. And if they slandered Nicholas II and in every way attempted to discredit his family, even when he reigned as autocrat and emperor, then how much worse were their attacks when all the emperor-in-exile had to defend him was his honour and his word?

In fairness, it must be said that many leaders of the emigration eventually reconsidered their views and stopped spreading false stories, and some asked for forgiveness and declared their loyalty to my grandfather or, if their change of heart happened later, my father. Among the most famous to do so was the philosopher Ivan Ilyin.

In 1992, President Boris Yeltsin restored to you and your family your Russian passports. Since that time, you have made numerous visits to Russia and met many people from all walks of life. Since that historic visit in 1992, what has Russia come to mean to you personally?

Russia is my homeland, and that says it all. I was raised from earliest childhood to feel this way.

I feel entirely at home both when I am in the various regions of Russia, or when I am in any of the other independent nations that arose after the fall of the USSR.

We of course fully recognize the current laws and sovereignty of these new states. But in a historical, spiritual, and cultural sense, all the peoples of the former Russian Empire have one homeland—they all belong to a single cultural space. Because of this, our fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers fought together, struggled together, and spilled their blood for their common home.

I travel to Russia more often than to some other places, and the Russian Imperial House is most active there. I am so pleased to see how the great majority of my countrymen, even those who do not share our views and values, nonetheless treat us with kindness, love, understanding, and warmth.

The work we do is completely unconnected to any form of politics. The projects we are involved in all relate to charity, to the strengthening of ethnic, religious and civil peace, to the forging of connections between the peoples of the former Russian Empire, to education, to the preservation of the historical legacy of our people, and the conservation of our nation’s natural environment, as well as other projects of this sort.

For nearly a century, the last Emperor of Russia, Nicholas II, has been maligned and slandered by Western historians and biographers. In your opinion, how have these historians and authors been mistaken about Nicholas II?

No one can prevent historical figures from being criticized.

But one must distinguish objective criticism from slander and defamation.

Both positive and negative assessments must be supported by evidence that emerges from the careful study and analysis of historical sources.

We are all judged by the fruits of our actions. Russia in the reign of Emperor Nicholas II grew in population by 150% and its rate of economic growth was the highest in the entire world. Labour laws in Russia were among the most progressive anywhere, which was acknowledged even by President Taft of the United States. The great Russian academic Dmitrii Mendeleev, the French economist Edmond Teri, and other researchers have written about the strength and development of Russia in these years and have shown that Nicholas II actually achieved a lot for his country during his reign.

Some might say that because the reign of Nicholas II ended in revolution, any accomplishments he may have had lose their value and meaning.

But that’s not the right way to look at it.

I think you would agree that, if a driver is unable to prevent a grenade from going off in his car, it doesn’t mean that he was a bad driver or that the car had some defect or had been poorly constructed or hadn’t been maintained in good working condition.

Absolutely—Emperor Nicholas II, like any human being or statesman, was not without sin and certainly did make mistakes.

But he was a man of deep faith, a great patriot, an honourable, genuine, and humane man, who with courage and integrity bore all the hardships that fate had delivered to him, both during his reign and afterward.

In canonizing him as a passion-bearer, the Holy Church affirmed that Emperor Nicholas II was one of the principal moral guides of our people. And I believe that this decision by the hierarchy of the Church resonates in the hearts of my countrymen.

Thus while I certainly do not deny the right of historians to debate the correctness or mistakes on this or that decision made by Emperor Nicholas II, I cannot condone those who try to blacken his memory or depict him as a dull and shallow-minded man who cared only about his family.

There is simply no substantiation in the historical sources for that view of him.

In your view, why is the rehabilitation of the Tsar-Martyr Emperor Nicholas II by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation so important for a proper understanding of Russian history?

Some misunderstand the meaning of the word “rehabilitation,” thinking that it connotes a kind of “amnesty.”

In point of fact, however, the rehabilitation of the victims of political repression is a recognition that such people were the targets of illegal action perpetrated in the name of the government and that these actions be deemed formally by the government today as illegal and the victims be recognized as having being entirely innocent and have their honour, integrity, and good name fully and legally restored to them.

For the Russian government today, the rehabilitation of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearer Emperor Nicholas II, his family, other murdered members of our House, and their faithful physician and attendants, has an enormous legal and moral significance.

The Russian Federation is the legal successor of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic—the RSFSR—and of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics—the USSR.

A local governmental organ, which exercised full political authority at that time—the Ural Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies—passed a death sentence on the Emperor, his family and their servants, and the supreme governmental organs of Soviet Russia—the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Soviet of People’s Commissars—recognized this decision as correct and approved it.

Until 2008, the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation had not ruled on my petition for the rehabilitation of the Royal Martyrs, and so from a legal point of view the executions continued to be considered lawful and justified.

Neither the canonization of the Royal Family by the Church nor the statements from various leaders of the country condemning the murders carried any legal weight. So we had a situation where the Church and the faithful considered Nicholas II and his family saints, many others of our countrymen considered them, if not saints, at least as innocent victims of terror, and the government? It saw them as criminals deserving of death.

Of course, that was an absurd and unsustainable situation—and a bloody burden from which the government needed to free itself.

Thank God, the highest court in the land concurred with the arguments I presented and finally made the correct and legal ruling on the matter.

I would especially like to acknowledge and thank the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Vyacheslav Lebedev, for his part in reaching this ruling. He delved deeply into the matter and put an end to this on-going violation of the law. Before the ruling came down on October 1, 2008, rehabilitating the murdered members of the Imperial Family, we did not know him at all or what he thought about our legal arguments or about us in general. But he researched the question on his own and agreed with my petition on its merits, issuing his ruling “On the Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression” entirely on the basis of the historical facts alone.

This ruling on the rehabilitation of the Imperial Family, their relatives and faithful servants, all murdered by the atheistic and totalitarian Communist regime, is perhaps one of the best pieces of evidence that Russia has undergone a colossal positive change in its understanding of the country’s past and has made important strides forward in the defense of human rights today.

Your father received a letter from Queen Elizabeth II and many other monarchs and heads of dynasties congratulating him on your birth in 1953. Do you continue maintain relations with members of the reigning and non-reigning royal house of Europe?

Yes, of course. After all, we are all related and so are in frequent contact with each other. As in any large family, I’m closer to some relatives more than others, and sometimes these relationships can affect official policy. I of course recognize that each monarch or head of a dynasty, and other members of royal houses must first and foremost serve the interests of his or her own country. And that’s how I conduct myself, as well. I offer all my strength and energy to defend the good name of Russia and to support my country in every way that I possibly can.

But at the same time, thanks to these familial ties linking our royal houses, we have the opportunity sometimes to help the international situation—easing tensions, facilitating communication, and helping to find compromises. Sometimes, the formerly reigning dynasties in this regard have even more influence than those that reign today because of the constraints that their positions sometimes place on the latter.

In this way, we can perform a kind of “people’s diplomacy,” initiated and carried out not through official channels, but through more informal cultural and philanthropic ones.

In December 2014, you were presented with the Order of St. Sergius of Radonezh 1st Class—the Church’s highest award—in recognition of your many years of work benefiting the Church. Can you reflect on your relationship with the Orthodox Church in post-Soviet Russia?

The connection between the House of Romanoff and the Orthodox Church is indissoluble. The decision to call our dynasty to the throne of Russia was made at the Great Council of 1613, which was not only an Assembly of the Land like other secular gatherings of the various territories and estates of the realm, but a local Church Council of the Russian Orthodox Church. It functioned as a Holy Council of the Church, with all metropolitans, archbishops, bishops, and abbots of the major monasteries participating.

According to the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, the Emperor or Empress cannot confess any other faith but Orthodoxy, and he or she is the defender and preserver of the doctrines of Orthodoxy, the guardian of its beliefs and of Church order.

After the Revolution, the historically close relationship between the Church and the Dynasty took on special significance. After all, the most severe persecutions were reserved not only for the monarchy and monarchists, but also for the faith and the faithful, as well as a whole range of traditional values.

During the years of exile, my grandfather and grandmother, my parents, and I and my son have lamented deeply the division of the Orthodox Church into jurisdictions and have striven always to restore the unity of the Church.

As soon as the opportunity presented itself, my father established contact with His Holiness Patriarch Aleksei II. From the first visit our family made to Russia, Patriarch Aleksei, the current Patriarch Kirill, and many other hierarchs and clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church have offered us their generous and unreserved spiritual and moral support in helping us to reintegrate into Russian society.

I worked to facilitate in any way I could the reunification of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad with the Mother-Church in Russia, which finally took place in 2007.

My son and I have enormous love and respect for His Holiness Patriarch Kirill. This very distinguished Orthodox hierarch is preserving the legacy of his predecessors and increasing the positive influence of the Church on the life of the state and society. He is an intercessor in prayer, a wise spiritual father, a brilliant homilist, and an experienced and effective Church administrator.

While maintaining our firm loyalty to Orthodoxy, my son and I have consistently supported good relations with our countrymen who confess other traditional faiths—Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism, for example. Our country has a rich history of inter-confessional cooperation and harmony, which we must continue to protect and promote going forward.

A new investigation into the Ekaterinburg remains opened in September 2015, one in which the Russian Orthodox Church is very much involved. The investigation also includes additional forensic tests on the remains. Why is this new investigation so important to the Church and the Russian Imperial House?

The disposition of the “Ekaterinburg Remains” continues to be an unresolved question, one which concerns millions of my countrymen.

The Russian government made a tremendous mistake in so quickly and definitively declaring these remains to be those of the Imperial Family and burying them in the Family Mausoleum of our House, even though there continued to exist serious doubts about their authenticity.

There were a number of procedural irregularities in the first study of the “Ekaterinburg Remains.” After the discovery of the burial location in the field known as Porosyonkov Log, or Piglet’s Ravine, in 1979, they were dug up, moved about, in part, to other locations, buried again—without any photos or videos documenting the excavations and without any attempt to log, or otherwise describe, the contents of the grave.

The questions that Patriarch Aleksei II submitted to researchers were given only perfunctory answers.

Nikolai Sokolov, the examining magistrate appointed by the White Government, carried out a painstaking investigation in 1919, shortly after the murders of the Emperor, his family and his entourage. The current investigation must carefully consider and seek to reconcile the evidence contained in the Sokolov report

It has been established that the gravesite had been disturbed before its official discovery. An unidentified cable was found on the site, as well as coins from the 1930s. It is very important to understand to what extent the gravesite may have been tampered with.

The Russian Orthodox Church has up to now not seen sufficient evidence to recognize the “Ekaterinburg Remains” as the relics of the Holy Royal Passion Bearers. In 1998, neither the Patriarch, nor the Metropolitan of St. Petersburg—indeed, not even one bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church—took part in the funeral of the “Ekaterinburg Remains” in the Ss. Peter and Paul Cathedral. Despite the presence of President Boris Yeltsin and many other senior officials of the government, priests, not hierarchs, officiated at the service. Names were not mentioned during the service, but rather the clergy prayed for "those whose names are known only to Thee, O Lord“—in other words, “only You know the names of those being buried here.” Those are the words used when the Orthodox Church prays for remains that have not been identified.

At the present time, the position of the Church has not changed.

And the Russian Imperial House entirely agrees with the position of the Church. On July 17, 1998, my mother, my son and I went to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra and attended the Divine Liturgy served by the Patriarch in order to demonstrate our solidarity with him.

First, as a loyal daughter of the Church, I cannot fail to support the Patriarch on a question so important to so many of the Orthodox faithful. Second, I am myself utterly convinced that, in matters such as this, there must not remain the slightest doubt or hint of deceit. And this is also the unwavering position of the Imperial House.

One must understand that there is no one in this world who more wants the authenticity of the “Ekaterinburg Remains” to be definitively determined than the Church and the dynasty.

The Church and the Imperial House has neither denied nor accepted the authenticity of the “Ekaterinburg Remains.” We hold out the hope that this question can be resolved one day.

For the Church, these physical remains would be holy relics offered to the people for pious veneration, and for us they would be that, and also the remains of our close and dear relatives. Their graves would become a place of pilgrimage for the faithful and a spiritual center for the advocates of the restoration of the monarchy.

But neither the Church nor the Imperial House can deceive the Russian people. A final determination of this question is impossible while there are still doubts. This is not political posturing or obscurantism or a distrust of science, but rather an expression of serious and responsible respect for history and for the religious feelings of people. The Church and the Imperial House are ancient institutions, and each operates in its own realm. They are not interested in any kinds of political shows for the sake of short-term goals, but are striving to establish the truth, no matter how long it takes.

Fortunately, last year an agreement was reached by which the entire matter will be investigated “from scratch.” Two commissions are working in parallel—a governmental commission and a Church commission. The grave of Nicholas II’s father, Emperor Alexander III, in the Ss. Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg was opened to obtain additional DNA samples. Work is also proceeding with the relevant historical documents, so that the many inconsistencies in them can be reconciled, if possible.

We are following these investigations very closely, as is the Church and all Russians, and we look forward to reviewing the results when they become available.

Russia has received a lot of criticism over the last two years because of the reunification of Crimea with the Russian Federation. What is your opinion of these events in Crimea and of the world’s reaction to them?

Crimea is not some empty expanse, but is populated with people. The people voted in a referendum to unite with Russia. And there is no evidence whatsoever that the referendum was tampered with or falsified.

It’s important to remember that Crimea had no historical connection whatsoever to Ukraine during the Russian Empire, nor to the Ukrainian SSR during Soviet times.

The decision to transfer Crimea (minus Sevastopol) into Ukraine was made by fiat by the leader of the totalitarian Communist regime, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1954. There were no polls taken, no referendum of the residents of Crimea at that time. It was done by the stroke of a pen.

After the fall of the USSR, the question of the Crimea was not taken up. People even forgot about the legal status of the city of Sevastopol, which remained a part of the Russian Federation.

Once could say that that was the result of the historic changes taking place and one just has to accept it. And in general, that is probably true. But I have visited Crimea twice when it was part of Ukraine, and I saw that the people of Crimea gravitated toward Russia culturally, yet remained entirely loyal citizens of Ukraine. And there was nothing bad about that because, as I already said, I am utterly convinced that the new boundaries and political circumstances today cannot destroy the underlying cultural unity that exists among the peoples of the former USSR and Russian Empire.

But after the 2014 revolution in Kiev, when the legally elected President of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych, was removed from office, the new government took actions and made public statements that clearly threatened the internal national and religious peace and stability of the country. There were attacks against the Russian-speaking population, persecution began against the clergy and faithful of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, and ugly anti-Semitism began to be seen.... This all occurred on the direct orders or with the clear approval of the politicians who had come to power in the wake of the ouster of President Yanukovych.

In these circumstances, the governmental authorities in Crimea, in full accord with the laws of Ukraine, took action to allow the people of Crimea to voice their opinions about the future of their peninsula. And the majority voted in a fully democratic process to unite Crimea with Russia.

With this referendum, Crimea avoided a potential civil war, which (given the complex international involvements in these events) could have been far bloodier and destructive that what we seen now in the Donets and Luhansk regions.

When people come to me and claim that there were legal and procedural problems with the referendum, I call their attention to two points.

First, the people who condemn this expression of the will of the people of Crimea in this referendum are the very same ones who recognized as legitimate the same expressions of popular will made, for example, in favour of the independence of Kosovo. Of course, there are a number of aspects of international law that make this an imperfect comparison, but even so a clear double standard is at work here: The Kosovars can declare their independence but the Crimeans cannot.

Second, and most important, the referendum in Crimea has helped to save thousands of lives. And this alone is enough to justify events—events that are rooted in history and current events.

Russia shares very close historical and spiritual ties with Ukraine. Many Russian Orthodox Christians still live in Ukraine. Diplomatic and political tensions between the two countries have deteriorated since the reunification. In your view, how can relations between Russia and Ukraine be improved?

The situation in Ukraine is for me and my son a source of tremendous anguish. Ukrainians, Russians, and Byelorussians are closely related peoples. Indeed, historically, these are three branches of the same people. It is a horrible thing when people kill one another, but it is even worse when the victims are one’s own brothers and sisters.

Right now, the path forward is murky and uncertain. For the past 25 years in Ukraine, an entire generation has grown up without any sense of the fundamental spiritual and cultural unity of the Slavic peoples. Many there see Russia as an enemy that is responsible for Ukraine’s current woes. These sentiments are whipped up by politicians and the media.

The blood that has been spilt on both sides in the conflict in the Donets and Luhansk regions pours from wounds that will not soon heal.

I am deeply concerned about, and pray for, all those who have perished or suffered during this conflict, and I mourn with the mothers, fathers, wives, sisters, and children—on both sides—who have lost their sons, husbands, brothers, and fathers. For me, the conflict in Ukraine is a senseless and tragic outbreak of a civil war, which has its ultimate origins in the Revolution of 1917.

I call upon all sides to come to their senses, to cease this mutual destruction, to ask each other for forgiveness, and to resolve the issues between them through negotiations, putting first in their hearts and minds not that which separates them, but that which unites them.

Only in this way will the bloodletting stop and mutual trust and cooperation be restored.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, there has been a growing interest in the Romanoff dynasty and their legacy in modern day Russia. Since that time, you have worked tirelessly to restore the name and the image of the Romanoff dynasty. Why is it so important for new generations of Russians to understand the contributions that the House of Romanoff made to Russia’s history and culture?

It is important not only to remember the contributions that our dynasty has made, but also to know the history of our country, to glean lessons from its past, to offer an accurate moral evaluation both of the good that happened and the bad, to try to avoid the mistakes of the past, and to use that past to chart a course for the nation moving forward.

We must also come to understand that in all ages, there are things we have done for which we must ask forgiveness. We are not always in the right on all things, and our enemies, competitors, and opponents are not always in the wrong. That means we must learn how to make an assessment not only of others, but also of ourselves. We must learn to hear and listen to others, and to recognize that they may be in the right, provided they can prove their point. We must learn to forgive those who have injured and offended us, and we must not fear to ask forgiveness of others.

Only in this way can we achieve national unity in our country and normal and peaceful coexistence with other nations.

So, when I talk about my ancestors, it is not only to praise them. I do not idealize this history of the rule of our House. To the contrary, I always say that while there is much to be proud of in our past, there is also much to regret, and so I do ask for forgiveness of God and of my people on my own behalf and on behalf of previous generations of the dynasty.

None of my countrymen are my enemies. Whether it be those who vehemently disagree with me, or those who are on the other side of an ideological divide, or acid critics of everything I hold most dear—all are my brothers and sisters. I stand ready at all times to meet and discuss the past, present and future with people of all views in order to find a way to work together to serve Russia.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, a growing number of Russians have raised the possibility of restoring the monarchy. The latest poll conducted in 2013 suggested that 28% of Russians would support a restoration of the monarchy. How could the monarchy benefit the nation and its people in the 21st century?

Monarchy is not some political form that is uniquely bound to only one era in history, but a timeless concept—the concept of the Family-State.

In our times, republics are the dominant form of government. I would call them State/Joint Stock Companies, or State/Businesses.

There was a time when people thought that monarchy—with all its paternalism and traditionalism—had become obsolete, and that republics were much more effective and progressive forms of government.

However, the global crisis, which only worsens each year, shows that republics and their underlying ideological system are not able to guarantee prosperity and stability. Quite the opposite—the problems are only mounting, growing like a snowball rolling down a hill.

Materialism, cynicism, self-indulgence, a sense of rootlessness, and the thoughtless abandonment of the legacies of the past—this is not the path to freedom and prosperity, but a quagmire where the spirit dies and the dignity of the individual is destroyed by the world around us.

In many countries people are beginning to understand this and to return again to traditional values.

If in the past the crisis of monarchy was an outgrowth of the general crisis of faith and tradition, then today the increasing interest in faith and tradition is in turn giving rise to greater interest in monarchy.

I am convinced that monarchy could be of use again both in Russia and in many other countries.

Hereditary monarchy offers continuity—living, purposeful continuity—with the past and can serve as a genuine neutral arbiter in society and politics because it is not beholden for its status and power to one party or political group. Monarchy advocates and protects the interests of the entire nation as a whole.

Were we to talk about progressive reforms and change, then again I would say that monarchy is a much more effective vehicle for modernization than republics. In Russia, one need only think of Peter I the Great, or Catherine II the Great, or Alexander II the Tsar-Liberator.

Monarchy is, I think, a much more human institution than a republic. Having gone through the experience of political revolutions which gave rise to the soulless all-encompassing State-Leviathan, humanity needs to restore a natural and organic state structure, which unites the people not only on the basis of “common interests” (or a “common economy”), as a republic does, but on the basis of a fundamental recognition that each nation is like a unified family; and that is a basis that monarchy can provide.

Of course, businesses can be healthy and prosperous and families can be sickly and dysfunctional.

But no rational person would exchange their family, no matter how many problems they had, for a business, no matter how successful it is.

In short, I believe there is a future for monarchy. But it would be a huge mistake to suggest that monarchy can be restored overnight, as a result of some political maneuvering.

The destruction of the monarchical mentality took many decades. Many of those who declare themselves in favour of monarchy today in fact do not understand what monarchy is, and what they really mean by the term monarchy is dictatorship or a mere figurehead.

Any decision to restore the monarchy can only be made by the majority of the people, and on the basis of an understanding and acceptance of the entire system of monarchical values, an understanding of history—both its achievements and failures, because all human systems of government will have both.

Without this, the restoration of the monarchy would not make much sense and would not last.

Restoring the monarchy will require a lot of patient work educating the public and that takes time. But even in a republic, the Imperial House can and does serve the nation, placing no preconditions on that service and not striving in any way either to speed up the process or somehow force ourselves on our country.

The Imperial House, and those of our countrymen who are loyal to it, must not attempt to rush events or bend our ideals to reap temporary political benefits, but to live according to the principle: “Always do the right thing, come what may.”

If Russia were again to be a monarchy, would you accept the throne?

If Russia again became a monarchy, the person who would ascend the throne would be the person who at that moment was the legitimate Head of the House of Romanoff. Whoever that is—me, my son, or someone in the next generation after that—will be fulfilling his or her duty.

The Romanoffs have never striven for power. The first tsar of our dynasty, Mikhail Fedorovich, received the news of his selection as tsar not with joy, but with great fear and reluctance. When Nicholas I in 1825 learned that he had become Emperor, his first words to his wife were: “My dearest, our quiet happy life has come to an end.”

We understand very well that power is not some coveted award, but rather a weighty burden. And those who ascribe to us an ambition for the throne are very much mistaken.

But the Lord has called our family to be the preservers of our nation’s historical continuity and of the ideals of the Orthodox Russian monarchy. If this ideal one day is once again taken up by our people, then we will not shirk from our ancestral responsibilities.

Will the Russian Imperial House seek restitution of the properties that were seized and nationalized during the Soviet period?

Like my father and grandfather before me, I have many times stated that I am in principle against the idea of any kind of restitution of properties.

Neither now, nor ever in the future, do I intend to request or demand back any of the properties that once belonged to my ancestors.

My grandfather, Emperor-in-Exile Kirill I, pointed out as early as the 1920s, not long after the revolution—when there were still alive many of the former owners of these properties or their direct heirs—the danger that any calls for the restitution of properties might introduce in the country.

Today, after a century has gone by, the restitution of properties is no longer even possible. The hypothetical advantages would be obviously and completely outweighed by the clear disadvantages. Restitution would give rise to a wave of new conflicts, which would only undermine national unity.

Only the Church and other traditional religious confessions in Russia have the right to have their churches, monasteries, and other buildings restored to them. These properties have from the beginning been dedicated to God and were built for purely religious purposes.

Clearly, having called on others to give up their claims to the restitution of properties for the good of society, I can hardly take a different position for myself.

If we are in one way or another to take up permanent residence in our country, the question of where we would live would not be answered by the restitution of property, but in a way that would not infringe on anyone else’s interests and that would not involve state expenditures.

In 2015 Vladimir Petrov, a member of the legislative assembly of the Leningrad Region, proposed the idea that members of the Russian Imperial House move to Russia to take up permanent residence there. Do you have any intentions to move to Russia?

Of course, we want to return to Russia and live there permanently. If we were ordinary private citizens, we could have done this long ago. But my son and I bear a responsibility to the future fate of the Russian Imperial House of Romanoff as an historical institution. Therefore, our permanent return can happen only after a number of legal questions are resolved.

The proposals and suggestions of some Russian politicians remain for now just that—proposals and suggestions. But the idea is certainly in the air, as the proposal you mentioned in your question shows.

We think it would be correct for the Russian government today to recognize officially the status of the Russian Imperial House as a historical institution: that is, as a family corporation which enjoys an unbroken history since coming to the throne in 1613, and which conducts its internal life and activities on the basis of its own historic House Laws to the extent that these laws do not conflict with the current laws of the Russian Federation.

This status would not entail any special privileges nor any political or economic advantages. The purpose of this official recognition by the government would be to restore the Imperial House to its rightful historical place and to recognize its continuity. Doing so would not conflict with the Constitution of the Russian Federation, but would rather directly complement the words of Article 44, which speaks of the preservation of the nation’s historical and cultural heritage.

But I repeat: we believe establishing the legal status of the Imperial House is a necessary and useful thing, but we do not place any preconditions to this. We understand that important decisions require time. We are gratified that we have the opportunity to visit our country and to participate in its life. We try to serve Russia in every way we can, and in the circumstances that exist now.

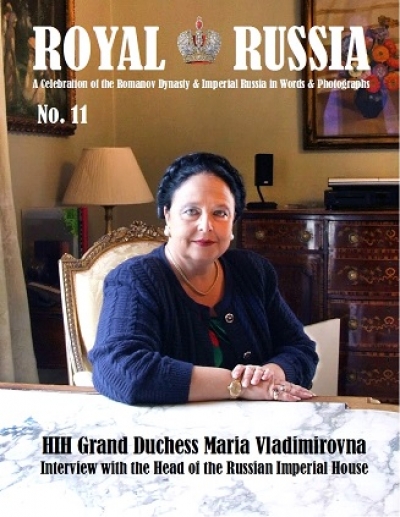

Next year marks the 25th anniversary since your ascension to the Head of the Russian Imperial House. What does this landmark anniversary mean to you?

Only this: that in the remaining years that God gives me I continue to serve in such a way that neither my ancestors nor my descendants would have reason not to be proud of me.

Links: